Muniratu Asiyanbi grinned from ear to ear, her multi-colored African wax fabric swinging slowly to the rhythm of the afternoon wind. She had just bought a bag of maize from the popular Odo-Ori market in Iwo, Osun State, after haggling prices with traders for several hours. But her enthusiasm wasn’t only driven by the prospect of the gains she would make from the sales of her maize, but by the nature of the source of her ‘capital’.

“Getting the money I just used to purchase my bag of maize was like a dream come through for me and many traders you see here today,” she said in her native Yoruba language, flashing me a toothy smile. “I got it from the election we held last Saturday and it was as if we should be holding governorship elections every day.”

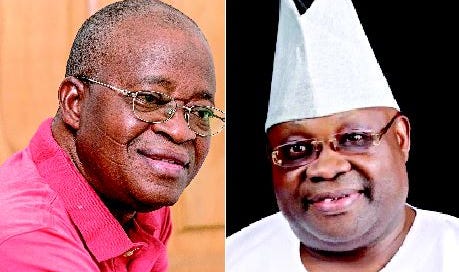

Days before I met Muniratu at the Odo-Ori market, people across the 30 local governments in Osun State had trooped out to cast their votes in a keenly contested governorship election. Although over a dozen candidates contested in the election, it was eventually a two-horses’ race between incumbent governor Gboyega Oyetola of the All Progressives Congress (APC) and Ademola Adeleke of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP).

On July 17, a day after the keenly contested election, the electoral commission, INEC, formally declared Ademola Adeleke of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) as the winner of the governorship election. INEC Chief Returning Officer for Osun, Oluwatoyin Ogundipe, who announced the result said the PDP candidate scored 403,371 votes to emerge victorious. The runner-up was the incumbent governor, Gboyega Oyetola of the All Progressives Congress (APC), who polled 375,027 votes.

Muniratu, who claimed that she cared less about the outcome of the election, confessed that the highlight of the governorship contest was the sharing of money for electorates by political actors across divides.

“I got N5,000 from the APC agent in our area and that was the best moment for me as far as this election is concerned,” she said, half-jokingly half-seriously.

But Muniratu isn’t even alone in her conception of the electoral contest as ‘fund-raising’ avenue in communities across the state. Multiple maize farmers I spoke with at local markets such as Odo-Ori and Oluwo markets in Iwo confessed that they got a chunk of the money with which they traded the next market day after the election from cash distributed to electorates during the Osun governorship election.

Traders at Odo-Ori market, Iwo, Osun State

Saliu Akanbi, a farmer and maize trader, told me that the people lost hope in the system and saw the money as the only “dividend” of democracy they could enjoy from politicians, hence, the widespread voters’ inducement recorded in the election.

“Many of our people got money on Saturday (election day) because that’s the only time we saw politicians come to us to canvass support,” he said with practice nonchalance.

“I got at least N4,000 from the PDP agent in my community and others too got theirs in Iwo and Ile-Ogbo. That’s why you see that the market is this crowded; people have money in their hands. And if they don’t collect it, how else would they get money to trade?”

Osun’s Economic Nightmare

Although Osun has recorded relative fiscal stability in recent years, the state has had it rough in terms of its finances—a development that affected growth and impacted the people negatively. In 2018, the state was the sixth most indebted of the 36 states of the federation, with external debt standing at $101.5 million and domestic debt of N148.1bn.

In August 2020, a BusinessDay report detailed how Osun flirted with insolvency by spending 91% of its FAAC to service debt in the first quarter of the year. The report showed how Osun state spent N91 of every N100 collected as revenue allocation from the Federation Accounts Allocation Committee (FAAC) to service accumulated debts that were left by Governor Oyetola’s predecessors, most notably Rauf Aregbesola.

But by December 2021, the foreign debt had declined to $99.9 million and the domestic debt came down to N134 billion, according to Nigeria’s Debt Management Office. While the government tried its possible best to instill fiscal stability and drive productivity, the debt burden and other socio-economic challenges remained albatrosses.

For instance, more capital projects, including, roads, education, housing, agriculture, industrialization, youths empowerment, among other critical infrastructural projects that could drive economic development were projected by the government in 2021 when it earmarked N76 billion, representing 58.7 percent of N129.7 billion total budget estimates proposed for 2022, for the projects.

*Candidates Oyetola, Adeleke and Lasun Yusuf of APC, PDP and LP, respectively

The budget, with recurrent expenditure (operating cost) of N53, 593,627,990, representing 41.30 percent, also had capital expenditure (CAPEX) of N76,162,822,800, representing 58.70 percent. That’s in addition to other economic initiatives designed to increase productivity and empower the people economically

But all of these efforts did little to address the people’s poverty, according to Mallam Shuaib, an Osogbo-based trader.

“The people barely understand the depth of the crisis in the state or the nation, so it is difficult to convince them that things are the way they are.,” he said.

Shuaib argues that if the rate of inflation and poverty are factored into the dynamics of electioneering, then the decision of the people to obtain money from politicians may not be out of place.

Poverty and Electoral Choice

Although Osun State government has tried to position the state in good financial position, the efforts have not translated much in the quality of life of the people.

In 2020, Osun’s IGR grew to N19.67 billion, placing it among the top 16 states with the highest IGRs in the country. The state raised N9.6 billion in the first six months of the year and N9.8 billion in the last six months. Yet on a per capita basis, the state’s IGR is relatively low compared to its peers, falling below the national average of N4,616. In fact, Osun state has the second-lowest IGR per capita in the South-West region, rankling 19th on the national scale.

“What this means is that there isn’t much activities going on to generate revenue for the government,” says Tola Agboola, an Ilesha-based trader. “Osun is a largely agrarian state and that’s why it reflects in the economic condition of the people. How then would they not be induced by politicians?”

Osun has 11.7 percent unemployment rate, considered the lowest in the country, yet when placed against the national unemployment rate of 33% as of 2020, the state might be battling with an army of unproductive youth like most states nationwide.

Similarly, Osun state had a poverty headcount ratio of 8.52 percent in 2018, the third lowest poverty headcount, according to the NBS ‘2019 Poverty and Inequality in Nigeria report, which was based on data from the Nigerian Living Standards Survey. Yet given that the national poverty rate has increased, Osun must have equally had to sink deeper into poverty within the years. Last year, for instance, the World Bank said the number of persons living in poverty in Nigeria would increase to 79 per cent.

Bashiru Ajadi, a policy analyst based in Ede, Osun West, believes that the twin tragedies of poverty and unemployment are drivers of electoral heist and vote-buying, because they make the people vulnerable to all manner of temptations.

“A man who is hungry would easily sell his votes to politicians, and that’s why we must call for good policies both at the state and federal level so that our people can make the right electoral decisions,” he says. “A situation where people vote to buy a bag of maize or cook a pot of soup is antithetical to the growth of our democracy.”

Protecting the Votes; Empowering the people

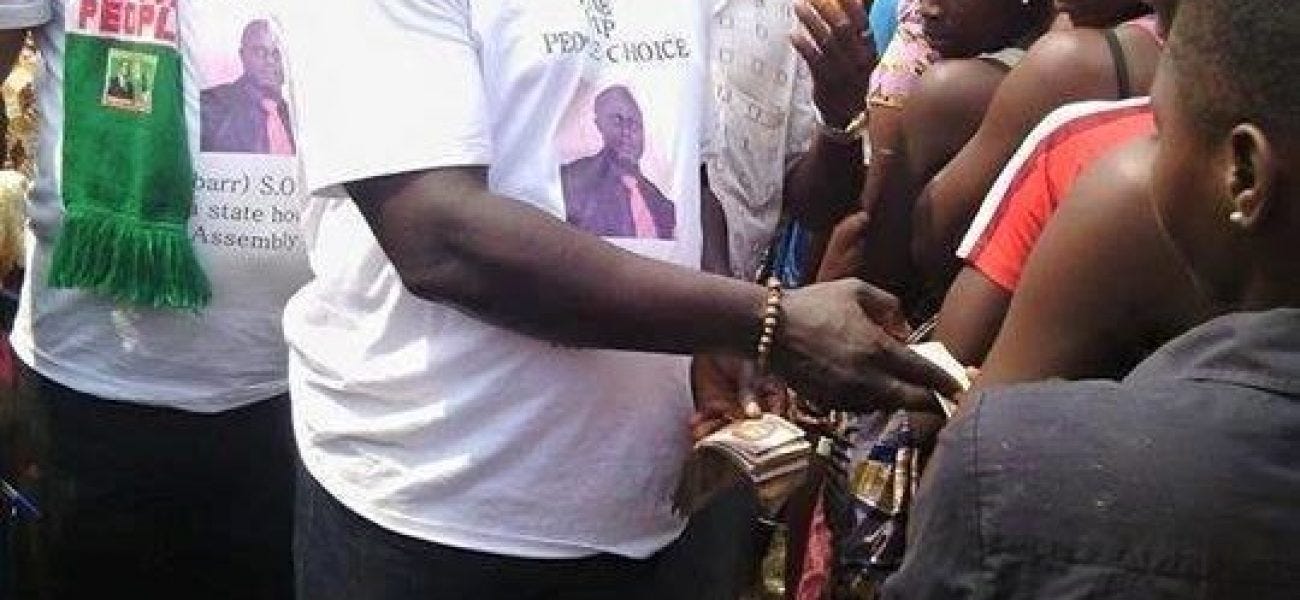

*Voter Inducement

On the eve of the Osun election, a voter who does not want to have his name in print told me about polling stations that were considered “lucrative” because the number of votes recorded there are often high. “Politicians always target these polling booths because they are very important and that’s why voters here get more money,” he said, reeling out the list of such polling units in Iwo and Ile-Ogbo communities.

Hours later, I drove past one of the listed communities, noticed a herd of scheming politicians hobnobbing with the crowd of people and confirmed that local politicians had already arranged for the disbursement of cash to electorates.

“On election day, I got N5000 cash from the parties,” the voter-source told me. “Some of my friends even got from both APC and PDP, making cool money.”

In its report on the Osun elections, an election monitoring group, YIAGA Africa commended the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) for the early arrival of polling officials and materials.

It however condemned acts of vote buying perpetrated by agents of the APC and PDP in some polling units.

“For instance, PU 009, Akinlalu Commercial Grammar School, Ward 01 in Ife North, the party agents strategically positioned themselves by the voting cubicle to see how voters marked their ballots,” YIAGA said in its report. “In PU 003 Opp. Olomu Mosque in Osogbo, PDP party agents were allegedly seen handing out between N2000 and N5000 to induce voters. Also, in Disu Polling Unit 003, ward 7 in Orolu LGA, APC agents were allegedly seen distributing N4000 to voters who voted for the party while PDP party agents were also allegedly seen distributing N2000 to induce voters.”

*Party agents arrested by the EFCC for alleged vote-buying in Osun

Mr Bashiru said that there is need for electorates to be empowered so they can make independent decisions: “The politicians are exploiting our peoples’ poverty and that’s why we must ensure that the people are empowered and taken out of poverty. It’s for the growth of our democracy.”

Akanbi on his part said that in the meantime, a clever way of reducing vote-buying is to mobilise massively for mass participation in the process, in such a way that it makes the act (vote-buying) quite expensive and unsustainable.

He said: “If people turn out massively for actual voting as much as they do for PvC registration, it will be very expensive to buy votes and politicians would be discouraged to go ahead. It wont end electoral malpractices but it can reduce it drastically.”

As the day metamorphoses slowly into night, Muniratu moves sluggishly away from our interview spot at Odo-Ori, calling on truck pushers to help carry her bag of maize. I joke about her business being “bankrolled” by a certain political party and she laughed it off, grinning yet again. She moved away from me slowly and said in Yoruba, with characteristic nonchalance: “When Nigeria treats us well and we can feed, we will begin to vote without collecting money from politicians.”